|

SPIRIT

LODGE

LIBRARY

Myth

& Lore

Page

27

|

(Main

Links of the site are right at the bottom of the page)

Some of the 86 pages in this Myth & Lore section are below.

The rest will be found HERE

Kokopelli: (or Kokopilau):

The Flute Player

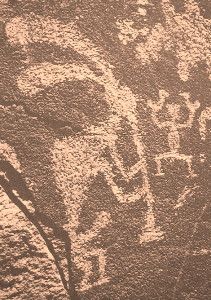

Kokopelli is a figure commonly found

in petroglyphs and pottery throughout the southwest. Since the

first petroglyphs were carved around 3,000 years ago, he predates

even Oraibi, the oldest continuous settlement in North America.

He is regarded as the universal symbol of fertility for all

life, be it crops, hopes, dreams, or love. Some legends suggest

that Kokopelli was an ancient Toltec trader who traveled routes

between Mexico, the west coast, the southwest, and possibly

even as far as the eastern areas of the U.S. Documented finds

lend truth to these legends as dentalium shells, which are only

found in certain coastal areas, and macaw feathers from Mexico

have been unearthed here in northern new Mexico and Arizona.

Kokopelli was said to play a flute

as he traveled to pronounce his arrival to the villagers and

it was considered the greatest of honors to be the women he

chose to be his "dreamtime companion" for his duration

of time in the village as many of these women apparently bore

children from these unions.

About Kokopelli Hopi legend tells

us that upon their entrance onto this, the fourth world, the

Hopi people were met by an Eagle who shot an arrow into the

two "mahus," insects which carried the power of heat.

They immediately began playing such uplifting melodies on their

flutes that they healed their own pierced bodies. The Hopi then

began their separate migrations and each "mahu" would

scatter seeds of fruits and vegetables onto the barren land.

Over them, each played his flute to bring warmth and make the

seeds grow.

His name -- KOKO for wood and Pilau

for hump (which was the bag of seeds he always carried)-- was

given to him on this long journey. It is said that he draws

that heat from the center of the Earth. He has come down to

us as the loving spirit of fertility -- of the Earth and humanity.

His invisible presence is felt whenever life come forth from

seed -- plants or animals.

A search of the web reveals the

extent of the commercialization of the Kokopelli image -- you

name it ... jewelry, sculpture, t-shirts, artwork ... and you'll

find him . Thus, I suppose he qualifies as one of the universal

symbols that Carl Jung talked about.

ON THE TRAIL OF KOKOPELLI

Text and Photos Jay W. Sharp The Southwest Indians’ Humpbacked

Flute Player, commonly known by the Hopi word "Kokopelli,"

usually appears on stone or ceramics or plaster as part of a

galaxy of ancient characters and symbols. On a steep canyon

wall above the Little Colorado river north of Springerville,

Arizona, however, a Kokopelli pecked into a basaltic boulder

appears in absolute isolation. Against the black rock surface

formed by primal forces, this strange and lonely figure, with

its apparent mal-formed back and long flute, seems to drift

through the infinite vastness of space, transcending time and

place, sending his plaintive music across the universe. There

is a sense of omnipresence, of the eternal. The early artist

– probably a shaman, or medicine man, seeking an entranceway

to the spirit world – may have understood a profound truth,

and he may have intentionally

used the surface to express the universality of that truth.

Of course, he may have simply used

the boulder’s surface as a convenient place to peck a Kokopelli

figure. There is no way to know with certainty what the artist

had in mind, but his work can set your imagination churning.

Kokopelli has stirred imaginations for a long time. Of the lexicon

of characters featured in the age-old religions, rituals, folk

tales, ceramics, rock art and murals of Southwestern Indians,

there are few more enduring than Kokopelli. He is so irresistibly

charismatic that he had been reinvented time and again for well

over 1000 years by southwestern artists, craftsmen and storytellers.

The process continues to this day. In the modern genre, he usually

wears a kilt and sash and a feathered headdress. Back arced

forward like a rainbow, he plays his ancient instrument. He

dances solemnly. He graces paintings, sculptures, ceramics,

jewelry, textiles and books in galleries and festivals in New

Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Colorado and western Texas. He is an

icon of the region.

In earlier times, Kokopelli was far

more than an icon. There is, in fact, considerable evidence

that he was an important deity to Southwestern Indians. His

images are among the most widely distributed of any in the prehistoric

and historic Indian sites of the Southwest. Kokopelli may have

been as important to the Southwestern Indians as Abraham is

to Jews or Paul, to Christians. Ubiquitous as the figure is,

the origins of Kokopelli as a deity and the evolution of his

role in Southwestern Indian life are difficult if not impossible

to reconstruct. It is like trying to assemble an immense and

mysterious jigsaw puzzle made up of a jumble of a few distinguishable

pieces, many indistinguishable pieces, innumerable missing pieces,

and numerous possibly unrelated pieces.

In classic form, a silhouetted and

sometimes phallic Kokopelli appears to either suffer a humped

back or to carry a bulging pack. He plays his flute like a New

Orleans jazz musician plays a clarinet. He may be depicted as

walking to some now unknown destination, lying on his back,

sitting with crossed legs, dancing to a prehistoric beat, making

love to a woman, even perching on the head of another figure

He appears in many forms. In Galisteo Basin rock art in New

Mexico, for instance, he takes on the guise of a humpbacked

rabbit.

At Sand Island, Utah, he appears

as a flute-playing mountain sheep. In rock art on West Mesa,

near Albuquerque, Kokopelli wears a headdress, necklaces and

a kilt. On rock art south of Holbrook, Arizona, he wears a kilt

and sash. On a prehistoric bowl from the Zuni reservation, he

appears as an insect, possibly the locust which led the Pueblo

people’s mythological emergence from the underworld onto

the surface of the earth. On rock art in the Arizona’s

Petrified Forest and Canyon de Chelly and near Moab, Utah, Kokopelli

turns up with a bird for a head. He is also represented in many

styles.

Unmistakable Kokopelli images in

rock art, for example, range

from stick figures in Chaco Canyon to spare, abstract stylizations

in Colorado’s San Canyon to simple outlines near Arizona’s

Hardscrabble Wash to solid figures near Velarde, New Mexico.

Elegant Kokopelli images painted on ceramics ten centuries ago

by the Hohokam, a southern Arizona Pueblo culture, have become

the prototype for modern portrayals. As indicated by his images,

Kokopelli seems to have played a featured role in numerous defining

moments of Southwestern Native American life. He leads processions

of people, perhaps on migrations. He participates with costumed

shaman figures in tribal rituals. He plays his flute for dances

in tribal ceremonies. He joins with other figures to illustrate

tribal myths. In hunting-magic scenes, he seeks to ensure success

for men carrying bows and, sometimes, lances. He impregnates

women. He participates in birthing scenes. Among ancient rain

and water symbols, he plays his flute to plead for moisture

sufficient for his tribe’s corn, beans and squash to grow.

On occasions, multiple Humpbacked

Flute Players appear in a single scene, perhaps seeking to redouble

chances for fertility and prosperity. Kokopelli’s guises,

styles and roles have mystified scholars for decades. They have

prompted divergent lines of research, given rise to diverse

theories, and led to some downright silly speculation. Yet another

layer of mystery about Kokopelli’s origin and evolution

lies in possible forerunners and derivatives. One possible forerunner

could have been simply flute players, lacking hump or phallus,

such as those which appear in Canyon de Chelly rock art dating

approximately 600 AD. Another possible related figures includes

a humpbacked, phallic figure which is shown carrying a staff

rather than playing a flute. One such example was painted on

a bowl fashioned by the Mimbres Indians of Southwestern New

Mexico some 900 to 1000 years ago. Yet another possible forerunner

includes humpbacked, phallic figures which carry bows rather

than play flutes. Such figures are painted on the wall of Fire

Temple in Mesa Verde National Park in Southwestern Colorado.

One of the more elaborate figures

which could be a Kokopelli-type derivative was pecked by an

18th century Navajo shaman into a canyon wall at a sacred site

in Northwestern New Mexico’s Largo drainage system. Surrounded

by other symbols chiseled into the rock, this regal figure stands

on muscled legs, wears a headdress and decorated kilt, and is

depicted holding a staff rather than playing a flute. He bears,

not a hump, but rather a rainbow-outlined pack adorned with

feathers and filled with seeds. This site, like other rock art

sites in the Largo Canyon complex, is still revered by traditional

Navajos. Vandals have defaced it in some areas, an act akin

to desecrating a church, a synagogue or a mosque. The relationships,

if any, between Kokopelli and those figures which feature only

a hump or just a flute is not clear and may never be clear.

The pieces of the jigsaw puzzle which

are available to us have produced endless and sometimes emotional

conjecture about Kokopelli’s origin and meaning. One possibility

is that Kokopelli could have been an actual misshapen person

who was widely venerated for his power and wisdom. He could

have been a young man, burdened with a pack, traveling among

pueblos, seeking a wife; he played his flute to announce his

mission. He could be a great leader, like Moses, who guided

his people in a migration to a new homeland. He could have been

a pochteca, a early bearer of gifts from central Mexico. One

of the more exotic theories was mentioned by southwestern Colorado

authority Michael Claypool during a discussion several years

ago at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado. He thinks that

origins of the figure could eventually be traced all the way

to Peru, where native traders carrying packs have long used

flutes to announce their arrival at native villages.

An archaeologist friend who has worked

in Latin America tells me that Kokopelli-like figures are common

icons in prehistoric sites of Southern Mexico and Central America.

While we may never know the origin or the full meaning of Kokopelli,

it is clear that he held high importance as a deity in the arid

American Southwest. His roles in scenes representing human reproduction,

crop growth and water suggest that the Southwestern Indians

associated him universally with fertility and prosperity. His

roles in hunting scenes, processions, rituals and ceremonies

suggest that the Indians connected him universally to their

physical and spiritual well-being. It is clear, too that the

magic of Kokopelli is enduring.

A few summers ago, my wife and I

came upon a dancing Kokopelli figure pecked high on the sandstone

canyon wall above the Chaco Canyon ruin known as Kin Kletso.

A thunderstorm rumbled threateningly overhead. You could almost

hear a plaintive and simple melody in the wind as Kokopelli

played his flute resolutely to plead for rain from the sky above

and to encourage the growth of crops of a long-vanished people

in the canyon bottom below.

There are many places to see Kokopelli

figures in rock art. Examples include West Mesa, across the

Rio Grande from Albuquerque; Canyon del Chelly, in northeastern

Arizona; Chaco Canyon, in northwestern New Mexico; and above

the Little Colorado River, near the Raven Site Ruin north of

Springerville, Arizona.

Kokopelli figures appear occasionally

on Indian pottery in Southwestern Indian museums.

Dennis Slifer and James Duffield present the best overview of

the Humpbacked Flute Player and locations in their book Kokopelli.

Polly Schaafsma provides

a good review of Southwestern rock art, with various reference

to Kokopelli, in her book Indian Rock Art of the Southwest.

Stephen W. Hill, author, and Robert B. Montoya, illustrator,

give a brief overview combined with excellent Kokopelli-inspired

illustrations in the book Kokopelli Ceremonies.

link:www.desertusa.com/mag00/apr/stories/trail_kok.html

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Libraries

are on this row

|

|

|

INDEX

Page 3

(Main Section, Medicine Wheel, Native Languages &

Nations, Symbology)

|

|

INDEX

Page 5

(Sacred Feminine & Masculine, Stones & Minerals)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

©

Copyright: Cinnamon Moon & River WildFire Moon (Founders.)

2000-date

All rights reserved.

Site

constructed by Dragonfly

Dezignz 1998-date

|

|